"The Shawshank Redemption" is a movie about time, patience and loyalty -- not sexy qualities, perhaps, but they grow on you during the subterranean progress of this story, which is about how two men serving life sentences in prison become friends and find a way to fight off despair.

The story is narrated by "Red" Redding (Morgan Freeman), who has been inside the walls of Shawshank Prison for a very long time and is its leading entrepreneur. He can get you whatever you need: cigarettes, candy, even a little rock pick like an amateur geologist might use. One day he and his fellow inmates watch the latest busload of prisoners unload, and they make bets on who will cry during their first night in prison, and who will not. Red bets on a tall, lanky guy named Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), who looks like a babe in the woods.

But Andy does not cry, and Red loses the cigarettes he wagered. Andy turns out to be a surprise to everyone in Shawshank, because within him is such a powerful reservoir of determination and strength that nothing seems to break him. Andy was a banker on the outside, and he's in for murder. He's apparently innocent, and there are all sorts of details involving his case, but after a while they take on a kind of unreality; all that counts inside prison is its own society -- who is strong, who is not -- and the measured passage of time.

Red is also a lifer. From time to time, measuring the decades, he goes up in front of the parole board, and they measure the length of his term (20 years, 30 years) and ask him if he thinks he has been rehabilitated. Oh, most surely, yes, he replies; but the fire goes out of his assurances as the years march past, and there is the sense that he has been institutionalized -- that, like another old lifer who kills himself after being paroled, he can no longer really envision life on the outside.

Red's narration of the story allows him to speak for all of the prisoners, who sense a fortitude and integrity in Andy that survives the years. Andy will not kiss butt. He will not back down. But he is not violent, just formidably sure of himself. For the warden (Bob Gunton), he is both a challenge and a resource; Andy knows all about bookkeeping and tax preparation, and before long he's been moved out of his prison job in the library and assigned to the warden's office, where he sits behind an adding machine and keeps tabs on the warden's ill-gotten gains. His fame spreads, and eventually he's doing the taxes and pension plans for most of the officials of the local prison system.

There are key moments in the film, as when Andy uses his clout to get some cold beers for his friends who are working on a roofing job. Or when he befriends the old prison librarian (James Whitmore). Or when he oversteps his boundaries and is thrown into solitary confinement. What quietly amazes everyone in the prison -- and us, too -- is the way he accepts the good and the bad as all part of some larger pattern than only he can fully see.

The partnership between the characters played by Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman is crucial to the way the story unfolds. This is not a "prison drama" in any conventional sense of the word. It is not about violence, riots or melodrama. The word "redemption" is in the title for a reason. The movie is based on a story, Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, by Stephen King, which is quite unlike most of King's work. The horror here is not of the supernatural kind, but of the sort that flows from the realization than 10, 20, 30 years of a man's life have unreeled in the same unchanging daily prison routine.

The director, Frank Darabont, paints the prison in drab grays and shadows, so that when key events do occur, they seem to have a life of their own.

Andy, as played by Robbins, keeps his thoughts to himself. Red, as Freeman plays him, is therefore a crucial element in the story: His close observation of this man, down through the years, provides the way we monitor changes and track the measure of his influence on those around him. And all the time there is something else happening, hidden and secret, which is revealed only at the end.

"The Shawshank Redemption" is not a depressing story, although I may have made it sound that way. There is a lot of life and humor in it, and warmth in the friendship that builds up between Andy and Red. There is even excitement and suspense, although not when we expect it. But mostly the film is an allegory about holding onto a sense of personal worth, despite everything. If the film is perhaps a little slow in its middle passages, maybe that is part of the idea, too, to give us a sense of the leaden passage of time, before the glory of the final redemption.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

The Social Network

"The Social Network" is about a young man who possessed an uncanny ability to look into a system of unlimited possibilities and sense a winning move. His name is Mark Zuckerberg, he created Facebook, he became a billionaire in his early 20s, and he reminds me of the chess prodigy Bobby Fischer. There may be a touch of Asperger's syndrome in both: They possess genius but are tone-deaf in social situations. Example: It is inefficient to seek romance by using strict logic to demonstrate your intellectual arrogance.

David Fincher's film has the rare quality of being not only as smart as its brilliant hero, but in the same way. It is cocksure, impatient, cold, exciting and instinctively perceptive.

It hurtles through two hours of spellbinding dialogue. It makes an untellable story clear and fascinating. It is said to be impossible to make a movie about a writer, because how can you show him only writing? It must also be impossible to make a movie about a computer programmer, because what is programming but writing in a language few people in the audience know? Yet Fincher and his writer, Aaron Sorkin, are able to explain the Facebook phenomenon in terms we can immediately understand, which is the reason 500 million of us have signed up.

To conceive of Facebook, Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) needed to know almost nothing about relationships or human nature (and apparently he didn't). What he needed was the ability to intuit a way to involve the human race in the Kevin Bacon Game. Remember that Kevin Bacon himself need not know more than a fraction of the people linking through him. Same on Facebook. I probably know 40 of my Facebook friends well, 100 glancingly, 200 by reputation. All the others are friends of friends. I can't remember the last time I received a Friend Request from anyone I didn't share at least one "Mutual Friend" with.

For the presence of Facebook, we possibly have to thank a woman named Erica (Rooney Mara). "The Social Network" begins with Erica's date with Zuckerberg. He nervously sips a beer and speed-talks through an aggressive interrogation. It's an exercise in sadistic conversational gamesmanship. Erica gets fed up, calls him an asshole and walks out.

Erica (a fictional character) is right, but at that moment she puts Zuckerberg in business. He goes home, has more beers and starts hacking into the "facebooks" of Harvard dorms to collect the head shots of campus women. He programs a page where they can be rated for their beauty. This is sexist and illegal, and proves so popular, it crashes the campus servers. After it's fertilized by a mundane website called "The Harvard Connection," Zuckerberg grows it into Facebook.

In theory, there are more possible moves on a chess board than molecules in the universe. Chessmasters cannot possibly calculate all of them, but using intuition, they can "see" a way through this near-infinity to a winning move. Nobody was ever better at chess than Bobby Fischer. Likewise, programming languages and techniques are widely known, but it was Zuckerberg who intuited how he could link them with a networking site. The genius of Facebook requires not psychological insight but its method of combining ego with interaction. Zuckerberg wanted to get revenge on all the women at Harvard. To do that, he involved them in a matrix that is still growing.

It's said there are child prodigies in only three areas: math, music and chess. These non-verbal areas require little maturity or knowledge of human nature, but a quick ability to perceive patterns, logical rules and linkages. I suspect computer programming may be a fourth area.

Zuckerberg may have had the insight that created Facebook, but he didn't do it alone in a room, and the movie gets a narration by cutting between depositions for lawsuits. Along the way, we get insights into the pecking order at Harvard, a campus where ability joins wealth and family as success factors. We meet the twins Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss (both played by Armie Hammer), rich kids who believe Zuckerberg stole their "Harvard Connection" in making Facebook. We meet Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield), Zuckerberg's roommate and best (only) friend, who was made CFO of the company, lent it the money that it needed to get started and was frozen out. And most memorably we meet Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), the founder of two legendary web startups, Napster and Plaxo.

It is the mercurial Parker, just out of work but basked in fame and past success, who grabbed Zuckerberg by the ears and pulled him into the big time. He explained why Facebook needed to move to Silicon Valley. Why more money would come from venture capitalists than Eduardo would ever raise with his hat-in-hand visits to wealthy New Yorkers. And he tried, not successfully, to introduce Zuckerberg into the fast lane: big offices, wild parties, women, the availability of booze and cocaine.

Zuckerberg was not seduced by his lifestyle. He was uninterested in money, stayed in modest houses, didn't fall into drugs. A subtext the movie never comments on is the omnipresence of attractive Asian women. Most of them are smart Harvard undergrads, two of them (allied with Sean) are Victoria's Secret models, one (Christy, played by Brenda Song) is Eduardo's girlfriend. Zuckerberg himself doesn't have much of a social life onscreen, misses parties, would rather work. He has such tunnel vision he doesn't even register when Sean redrafts the financial arrangements to write himself in and Eduardo out.

The testimony in the depositions makes it clear there is a case to be made against Zuckerberg, many of them sins of omission. It's left to the final crawl to explain how they turned out. The point is to show an interaction of undergraduate chaos, enormous amounts of money and manic energy.

In an age when movie dialogue is dumbed and slowed down to suit slow-wits in the audience, the dialogue here has the velocity and snap of screwball comedy. Eisenberg, who has specialized in playing nice or clueless, is a heat-seeking missile in search of his own goals. Timberlake pulls off the tricky assignment of playing Sean Parker as both a hot shot and someone who engages Zuckerberg as an intellectual equal. Andrew Garfield evokes an honest friend who is not the right man to be CFO of the company that took off without him, but deserves sympathy.

"The Social Network" is a great film not because of its dazzling style or visual cleverness, but because it is splendidly well-made. Despite the baffling complications of computer programming, web strategy and big finance, Aaron Sorkin's screenplay makes it all clear, and we don't follow the story so much as get dragged along behind it. I saw it with an audience that seemed wrapped up in an unusual way: It was very, very interested.

David Fincher's film has the rare quality of being not only as smart as its brilliant hero, but in the same way. It is cocksure, impatient, cold, exciting and instinctively perceptive.

It hurtles through two hours of spellbinding dialogue. It makes an untellable story clear and fascinating. It is said to be impossible to make a movie about a writer, because how can you show him only writing? It must also be impossible to make a movie about a computer programmer, because what is programming but writing in a language few people in the audience know? Yet Fincher and his writer, Aaron Sorkin, are able to explain the Facebook phenomenon in terms we can immediately understand, which is the reason 500 million of us have signed up.

To conceive of Facebook, Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) needed to know almost nothing about relationships or human nature (and apparently he didn't). What he needed was the ability to intuit a way to involve the human race in the Kevin Bacon Game. Remember that Kevin Bacon himself need not know more than a fraction of the people linking through him. Same on Facebook. I probably know 40 of my Facebook friends well, 100 glancingly, 200 by reputation. All the others are friends of friends. I can't remember the last time I received a Friend Request from anyone I didn't share at least one "Mutual Friend" with.

For the presence of Facebook, we possibly have to thank a woman named Erica (Rooney Mara). "The Social Network" begins with Erica's date with Zuckerberg. He nervously sips a beer and speed-talks through an aggressive interrogation. It's an exercise in sadistic conversational gamesmanship. Erica gets fed up, calls him an asshole and walks out.

Erica (a fictional character) is right, but at that moment she puts Zuckerberg in business. He goes home, has more beers and starts hacking into the "facebooks" of Harvard dorms to collect the head shots of campus women. He programs a page where they can be rated for their beauty. This is sexist and illegal, and proves so popular, it crashes the campus servers. After it's fertilized by a mundane website called "The Harvard Connection," Zuckerberg grows it into Facebook.

In theory, there are more possible moves on a chess board than molecules in the universe. Chessmasters cannot possibly calculate all of them, but using intuition, they can "see" a way through this near-infinity to a winning move. Nobody was ever better at chess than Bobby Fischer. Likewise, programming languages and techniques are widely known, but it was Zuckerberg who intuited how he could link them with a networking site. The genius of Facebook requires not psychological insight but its method of combining ego with interaction. Zuckerberg wanted to get revenge on all the women at Harvard. To do that, he involved them in a matrix that is still growing.

It's said there are child prodigies in only three areas: math, music and chess. These non-verbal areas require little maturity or knowledge of human nature, but a quick ability to perceive patterns, logical rules and linkages. I suspect computer programming may be a fourth area.

Zuckerberg may have had the insight that created Facebook, but he didn't do it alone in a room, and the movie gets a narration by cutting between depositions for lawsuits. Along the way, we get insights into the pecking order at Harvard, a campus where ability joins wealth and family as success factors. We meet the twins Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss (both played by Armie Hammer), rich kids who believe Zuckerberg stole their "Harvard Connection" in making Facebook. We meet Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield), Zuckerberg's roommate and best (only) friend, who was made CFO of the company, lent it the money that it needed to get started and was frozen out. And most memorably we meet Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), the founder of two legendary web startups, Napster and Plaxo.

It is the mercurial Parker, just out of work but basked in fame and past success, who grabbed Zuckerberg by the ears and pulled him into the big time. He explained why Facebook needed to move to Silicon Valley. Why more money would come from venture capitalists than Eduardo would ever raise with his hat-in-hand visits to wealthy New Yorkers. And he tried, not successfully, to introduce Zuckerberg into the fast lane: big offices, wild parties, women, the availability of booze and cocaine.

Zuckerberg was not seduced by his lifestyle. He was uninterested in money, stayed in modest houses, didn't fall into drugs. A subtext the movie never comments on is the omnipresence of attractive Asian women. Most of them are smart Harvard undergrads, two of them (allied with Sean) are Victoria's Secret models, one (Christy, played by Brenda Song) is Eduardo's girlfriend. Zuckerberg himself doesn't have much of a social life onscreen, misses parties, would rather work. He has such tunnel vision he doesn't even register when Sean redrafts the financial arrangements to write himself in and Eduardo out.

The testimony in the depositions makes it clear there is a case to be made against Zuckerberg, many of them sins of omission. It's left to the final crawl to explain how they turned out. The point is to show an interaction of undergraduate chaos, enormous amounts of money and manic energy.

In an age when movie dialogue is dumbed and slowed down to suit slow-wits in the audience, the dialogue here has the velocity and snap of screwball comedy. Eisenberg, who has specialized in playing nice or clueless, is a heat-seeking missile in search of his own goals. Timberlake pulls off the tricky assignment of playing Sean Parker as both a hot shot and someone who engages Zuckerberg as an intellectual equal. Andrew Garfield evokes an honest friend who is not the right man to be CFO of the company that took off without him, but deserves sympathy.

"The Social Network" is a great film not because of its dazzling style or visual cleverness, but because it is splendidly well-made. Despite the baffling complications of computer programming, web strategy and big finance, Aaron Sorkin's screenplay makes it all clear, and we don't follow the story so much as get dragged along behind it. I saw it with an audience that seemed wrapped up in an unusual way: It was very, very interested.

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Zodiac

'Zodiac" is the "All the President's Men" of serial killer movies, with Woodward and Bernstein played by a cop and a cartoonist. It's not merely "based" on California's infamous Zodiac killings, but seems to exude the very stench and provocation of the case. The killer, who was never caught, generously supplied so many clues that Sherlock Holmes might have cracked the case in his sitting room. But only a newspaper cartoonist was stubborn enough, and tunneled away long enough, to piece together a convincing case against a man who was perhaps guilty.

The film is a police procedural crossed with a newspaper movie, but free of most of the cliches of either. Its most impressive accomplishment is to gather a bewildering labyrinth of facts and suspicions over a period of years, and make the journey through this maze frightening and suspenseful. I could imagine becoming hopelessly mired in the details of the Zodiac investigation, but director David Fincher ("Se7en") and his writer, James Vanderbilt, find their way with clarity through the murk. In a film with so many characters, the casting by Laray Mayfield is also crucial; like the only eyewitness in the case, we remember a face once we've seen it.

The film opens with a sudden, brutal, bloody killing, followed by others not too long after -- five killings the police feel sure Zodiac committed, although others have been attributed to him. But this film will not be a bloodbath. The killer does his work in the earlier scenes of the film, and then, when he starts sending encrypted letters to newspapers, the police and reporters try to do theirs.

The two lead inspectors on the case are David Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) and William Armstrong (Anthony Edwards). Toschi, famous at the time, tutored Steve McQueen for "Bullitt" and was the role model for Clint Eastwood's Dirty Harry. Ruffalo plays him not as a hotshot but as a dogged officer who does things by the book because he believes in the book. Edwards' character, his partner, is more personally worn down by the sheer vicious nature of the killer and his taunts.

At the San Francisco Chronicle, although we meet several staffers, the key players are ace reporter Paul Avery (Robert Downey Jr., bearded, chain-smoking, alcoholic) and editorial cartoonist Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal). These characters are real, and indeed the film is based on Graysmith's books about the case.

I found the newspaper office intriguing in its accuracy. For one thing, it is usually fairly empty, and it was true on a morning paper in those days that the office began to heat up closer to deadline Among the few early arrivals would have been the cartoonist, who was expected to work up a few ideas for presentation at the daily news meeting, and the office alcoholics, perhaps up all night, or already starting their recovery drinking. Yes, reporters drank at their desks 40 years ago, and smoked and smoked and smoked.

Graysmith is new on the staff when the first cipher arrives. He's like the curious new kid in school fascinated by the secrets of the big boys. He doodles with a copy of the cipher, and we think he'll solve it, but he doesn't. He strays off his beat by eavesdropping on cops and reporters, making friends with the boozy Avery, and even talking his way into police evidence rooms. Long after the investigation has cooled, his obsession remains, eventually driving his wife (Chloe Sevigny) to move herself and their children in with her mom. Graysmith seems oblivious to the danger he may be drawing into his home, even after he appears on TV and starts hearing heavy breathing over the phone.

What makes "Zodiac" authentic is the way it avoids chases, shootouts, grandstanding and false climaxes, and just follows the methodical progress of police work. Just as Woodward and Bernstein knocked on many doors and made many phone calls and met many very odd people, so do the cops and Graysmith walk down strange pathways in their investigation. Because Graysmith is unarmed and civilian, we become genuinely worried about his naivete and risk-taking, especially during a trip to a basement that is, in its way, one of the best scenes I've ever seen along those lines.

Fincher gives us times, days and dates at the bottom of the screen, which serve only to underline how the case seems to stretch out to infinity. There is even time-lapse photography showing the Transamerica building going up. Everything leads up to a heart-stopping moment when two men look, simply look, at one another. It is a more satisfying conclusion than Dirty Harry shooting Zodiac dead, say, in a football stadium.

Fincher is not the first director you would associate with this material. In 1992, at 30, he directed "Alien 3," which was the least of the Alien movies, but even then had his eye ("Alien 3" is one of the best-looking bad movies I have ever seen). His credits include "Se7en" (1995), a superb film about another serial killer with a pattern to his crimes; "The Game" (1997), with Michael Douglas caught in an ego-smashing web; "Fight Club" (1999), beloved by most, not by me; the ingenious terror of Jodie Foster in "Panic Room" (2002), and now, five years between features, his most thoughtful, involving film.

He seems to be in reaction against the slice-and-dice style of modern crime movies; his composition and editing are more classical, and he doesn't use nine shots when one will do. (If this same material had been put through an Avid to chop the footage into five times as many shots, we would have been sending our own ciphers to the studio.) Fincher is an elegant stylist on top of everything else, and here he finds the right pace and style for a story about persistence in the face of evil. I am often fascinated by true crime books, partly because of the way they amass ominous details (the best I've read is Blood and Money, by Tommy Thompson), and Fincher understands that true crime is not the same genre as crime action. That he makes every character a distinct individual is proof of that; consider the attention given to Graysmith's choice of mixed drink.

The film is a police procedural crossed with a newspaper movie, but free of most of the cliches of either. Its most impressive accomplishment is to gather a bewildering labyrinth of facts and suspicions over a period of years, and make the journey through this maze frightening and suspenseful. I could imagine becoming hopelessly mired in the details of the Zodiac investigation, but director David Fincher ("Se7en") and his writer, James Vanderbilt, find their way with clarity through the murk. In a film with so many characters, the casting by Laray Mayfield is also crucial; like the only eyewitness in the case, we remember a face once we've seen it.

The film opens with a sudden, brutal, bloody killing, followed by others not too long after -- five killings the police feel sure Zodiac committed, although others have been attributed to him. But this film will not be a bloodbath. The killer does his work in the earlier scenes of the film, and then, when he starts sending encrypted letters to newspapers, the police and reporters try to do theirs.

The two lead inspectors on the case are David Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) and William Armstrong (Anthony Edwards). Toschi, famous at the time, tutored Steve McQueen for "Bullitt" and was the role model for Clint Eastwood's Dirty Harry. Ruffalo plays him not as a hotshot but as a dogged officer who does things by the book because he believes in the book. Edwards' character, his partner, is more personally worn down by the sheer vicious nature of the killer and his taunts.

At the San Francisco Chronicle, although we meet several staffers, the key players are ace reporter Paul Avery (Robert Downey Jr., bearded, chain-smoking, alcoholic) and editorial cartoonist Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal). These characters are real, and indeed the film is based on Graysmith's books about the case.

I found the newspaper office intriguing in its accuracy. For one thing, it is usually fairly empty, and it was true on a morning paper in those days that the office began to heat up closer to deadline Among the few early arrivals would have been the cartoonist, who was expected to work up a few ideas for presentation at the daily news meeting, and the office alcoholics, perhaps up all night, or already starting their recovery drinking. Yes, reporters drank at their desks 40 years ago, and smoked and smoked and smoked.

Graysmith is new on the staff when the first cipher arrives. He's like the curious new kid in school fascinated by the secrets of the big boys. He doodles with a copy of the cipher, and we think he'll solve it, but he doesn't. He strays off his beat by eavesdropping on cops and reporters, making friends with the boozy Avery, and even talking his way into police evidence rooms. Long after the investigation has cooled, his obsession remains, eventually driving his wife (Chloe Sevigny) to move herself and their children in with her mom. Graysmith seems oblivious to the danger he may be drawing into his home, even after he appears on TV and starts hearing heavy breathing over the phone.

What makes "Zodiac" authentic is the way it avoids chases, shootouts, grandstanding and false climaxes, and just follows the methodical progress of police work. Just as Woodward and Bernstein knocked on many doors and made many phone calls and met many very odd people, so do the cops and Graysmith walk down strange pathways in their investigation. Because Graysmith is unarmed and civilian, we become genuinely worried about his naivete and risk-taking, especially during a trip to a basement that is, in its way, one of the best scenes I've ever seen along those lines.

Fincher gives us times, days and dates at the bottom of the screen, which serve only to underline how the case seems to stretch out to infinity. There is even time-lapse photography showing the Transamerica building going up. Everything leads up to a heart-stopping moment when two men look, simply look, at one another. It is a more satisfying conclusion than Dirty Harry shooting Zodiac dead, say, in a football stadium.

Fincher is not the first director you would associate with this material. In 1992, at 30, he directed "Alien 3," which was the least of the Alien movies, but even then had his eye ("Alien 3" is one of the best-looking bad movies I have ever seen). His credits include "Se7en" (1995), a superb film about another serial killer with a pattern to his crimes; "The Game" (1997), with Michael Douglas caught in an ego-smashing web; "Fight Club" (1999), beloved by most, not by me; the ingenious terror of Jodie Foster in "Panic Room" (2002), and now, five years between features, his most thoughtful, involving film.

He seems to be in reaction against the slice-and-dice style of modern crime movies; his composition and editing are more classical, and he doesn't use nine shots when one will do. (If this same material had been put through an Avid to chop the footage into five times as many shots, we would have been sending our own ciphers to the studio.) Fincher is an elegant stylist on top of everything else, and here he finds the right pace and style for a story about persistence in the face of evil. I am often fascinated by true crime books, partly because of the way they amass ominous details (the best I've read is Blood and Money, by Tommy Thompson), and Fincher understands that true crime is not the same genre as crime action. That he makes every character a distinct individual is proof of that; consider the attention given to Graysmith's choice of mixed drink.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Requests

I'm now taking requests for my next review. Just leave a comment, and tell me what movie you would like to see reviewed next. I will try to review all of the ones you request, starting with the most popular choice.

Inception

It's said that Christopher Nolan spent ten years writing his screenplay for "Inception." That must have involved prodigious concentration, like playing blindfold chess while walking a tight-wire. The film's hero tests a young architect by challenging her to create a maze, and Nolan tests us with his own dazzling maze. We have to trust him that he can lead us through, because much of the time we're lost and disoriented. Nolan must have rewritten this story time and again, finding that every change had a ripple effect down through the whole fabric.

The story can either be told in a few sentences, or not told at all. Here is a movie immune to spoilers: If you knew how it ended, that would tell you nothing unless you knew how it got there. And telling you how it got there would produce bafflement. The movie is all about process, about fighting our way through enveloping sheets of reality and dream, reality within dreams, dreams without reality. It's a breathtaking juggling act, and Nolan may have considered his "Memento" (2000) a warm-up; he apparently started this screenplay while filming that one. It was the story of a man with short-term memory loss, and the story was told backwards.

Like the hero of that film, the viewer of "Inception" is adrift in time and experience. We can never even be quite sure what the relationship between dream time and real time is. The hero explains that you can never remember the beginning of a dream, and that dreams that seem to cover hours may only last a short time. Yes, but you don't know that when you’re dreaming. And what if you're inside another man's dream? How does your dream time synch with his? What do you really know?

Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) is a corporate raider of the highest order. He infiltrates the minds of other men to steal their ideas. Now he is hired by a powerful billionaire to do the opposite: To introduce an idea into a rival's mind, and do it so well he believes it is his own. This has never been done before; our minds are as alert to foreign ideas as our immune system is to pathogens. The rich man, named Saito (Ken Watanabe), makes him an offer he can't refuse, an offer that would end Cobb's forced exile from home and family.

Cobb assembles a team, and here the movie relies on the well-established procedures of all heist movies. We meet the people he will need to work with: Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), his longtime associate; Eames (Tom Hardy), a master at deception; Yusuf (Dileep Rao), a master chemist. And there is a new recruit, Ariadne (Ellen Page), a brilliant young architect who is a prodigy at creating spaces. Cobb also goes to touch base with his father-in-law Miles (Michael Caine), who knows what he does and how he does it. These days Michael Caine need only appear on a screen and we assume he's wiser than any of the other characters. It's a gift.

But wait. Why does Cobb need an architect to create spaces in dreams? He explains to her. Dreams have a shifting architecture, as we all know; where we seem to be has a way of shifting. Cobb's assignment is the "inception" (or birth, or wellspring) of a new idea in the mind of another young billionaire, Robert Fischer Jr. (Cillian Murphy), heir to his father's empire. Saito wants him to initiate ideas that will lead to the surrender of his rival's corporation. Cobb needs Ariadne

to create a deceptive maze-space in Fischer's dreams so that (I think) new thoughts can slip in unperceived. Is it a coincidence that Ariadne is named for the woman in Greek mythology who helped Theseus escape from the Minotaur's labyrinth?

Cobb tutors Ariadne on the world of dream infiltration, the art of controlling dreams and navigating them. Nolan uses this as a device for tutoring us as well. And also as the occasion for some of the movie's astonishing special effects, which seemed senseless in the trailer but now fit right in. The most impressive to me takes place (or seems to) in Paris, where the city literally rolls back on itself like a roll of linoleum tile.

Protecting Fischer are any number of gun-wielding bodyguards, who may be working like the mental equivalent of antibodies; they seem alternatively real and figurative, but whichever they are, they lead to a great many gunfights, chase scenes and explosions, which is the way movies depict conflict these days. So skilled is Nolan that he actually got me involved in one of his chases, when I thought I was relatively immune to scenes that have become so standard. That was because I cared about who was chasing and being chased.

If you've seen any advertising at all for the film, you know that its architecture has a way of disregarding gravity. Buildings tilt. Streets coil. Characters float. This is all explained in the narrative. The movie is a perplexing labyrinth without a simple through-line, and is sure to inspire truly endless analysis on the web.

Nolan helps us with an emotional thread. The reason Cobb is motivated to risk the dangers of inception is because of grief and guilt involving his wife Mal (Marion Cotillard), and their two children. More I will not (in a way, cannot) say. Cotillard beautifully embodies the wife in an idealized way. Whether we are seeing Cobb's memories or his dreams is difficult to say--even, literally, in the last shot. But she makes Mal function as an emotional magnet, and the love between the two provides an emotional constant in Cobb's world, which is otherwise ceaselessly shifting.

"Inception" works for the viewer, in a way, like the world itself worked for Leonard, the hero of "Memento." We are always in the Now. We have made some notes while getting Here, but we are not quite sure where Here is. Yet matters of life, death and the heart are involved--oh, and those multi-national corporations, of course. And Nolan doesn't pause before using well-crafted scenes from spycraft or espionage, including a clever scheme on board a 747 (even explaining why it must be a 747).

The movies often seem to come from the recycling bin these days: Sequels, remakes, franchises. "Inception" does a difficult thing. It is wholly original, cut from new cloth, and yet structured with action movie basics so it feels like it makes more sense than (quite possibly) it does. I thought there was a hole in "Memento:" How does a man with short-term memory loss remember he has short-term memory loss? Maybe there's a hole in "Inception" too, but I can't find it. Christopher Nolan reinvented "Batman." This time he isn't reinventing anything. Yet few directors will attempt to recycle "Inception." I think when Nolan left the labyrinth, he threw away the map.

The story can either be told in a few sentences, or not told at all. Here is a movie immune to spoilers: If you knew how it ended, that would tell you nothing unless you knew how it got there. And telling you how it got there would produce bafflement. The movie is all about process, about fighting our way through enveloping sheets of reality and dream, reality within dreams, dreams without reality. It's a breathtaking juggling act, and Nolan may have considered his "Memento" (2000) a warm-up; he apparently started this screenplay while filming that one. It was the story of a man with short-term memory loss, and the story was told backwards.

Like the hero of that film, the viewer of "Inception" is adrift in time and experience. We can never even be quite sure what the relationship between dream time and real time is. The hero explains that you can never remember the beginning of a dream, and that dreams that seem to cover hours may only last a short time. Yes, but you don't know that when you’re dreaming. And what if you're inside another man's dream? How does your dream time synch with his? What do you really know?

Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) is a corporate raider of the highest order. He infiltrates the minds of other men to steal their ideas. Now he is hired by a powerful billionaire to do the opposite: To introduce an idea into a rival's mind, and do it so well he believes it is his own. This has never been done before; our minds are as alert to foreign ideas as our immune system is to pathogens. The rich man, named Saito (Ken Watanabe), makes him an offer he can't refuse, an offer that would end Cobb's forced exile from home and family.

Cobb assembles a team, and here the movie relies on the well-established procedures of all heist movies. We meet the people he will need to work with: Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), his longtime associate; Eames (Tom Hardy), a master at deception; Yusuf (Dileep Rao), a master chemist. And there is a new recruit, Ariadne (Ellen Page), a brilliant young architect who is a prodigy at creating spaces. Cobb also goes to touch base with his father-in-law Miles (Michael Caine), who knows what he does and how he does it. These days Michael Caine need only appear on a screen and we assume he's wiser than any of the other characters. It's a gift.

But wait. Why does Cobb need an architect to create spaces in dreams? He explains to her. Dreams have a shifting architecture, as we all know; where we seem to be has a way of shifting. Cobb's assignment is the "inception" (or birth, or wellspring) of a new idea in the mind of another young billionaire, Robert Fischer Jr. (Cillian Murphy), heir to his father's empire. Saito wants him to initiate ideas that will lead to the surrender of his rival's corporation. Cobb needs Ariadne

to create a deceptive maze-space in Fischer's dreams so that (I think) new thoughts can slip in unperceived. Is it a coincidence that Ariadne is named for the woman in Greek mythology who helped Theseus escape from the Minotaur's labyrinth?

Cobb tutors Ariadne on the world of dream infiltration, the art of controlling dreams and navigating them. Nolan uses this as a device for tutoring us as well. And also as the occasion for some of the movie's astonishing special effects, which seemed senseless in the trailer but now fit right in. The most impressive to me takes place (or seems to) in Paris, where the city literally rolls back on itself like a roll of linoleum tile.

Protecting Fischer are any number of gun-wielding bodyguards, who may be working like the mental equivalent of antibodies; they seem alternatively real and figurative, but whichever they are, they lead to a great many gunfights, chase scenes and explosions, which is the way movies depict conflict these days. So skilled is Nolan that he actually got me involved in one of his chases, when I thought I was relatively immune to scenes that have become so standard. That was because I cared about who was chasing and being chased.

If you've seen any advertising at all for the film, you know that its architecture has a way of disregarding gravity. Buildings tilt. Streets coil. Characters float. This is all explained in the narrative. The movie is a perplexing labyrinth without a simple through-line, and is sure to inspire truly endless analysis on the web.

Nolan helps us with an emotional thread. The reason Cobb is motivated to risk the dangers of inception is because of grief and guilt involving his wife Mal (Marion Cotillard), and their two children. More I will not (in a way, cannot) say. Cotillard beautifully embodies the wife in an idealized way. Whether we are seeing Cobb's memories or his dreams is difficult to say--even, literally, in the last shot. But she makes Mal function as an emotional magnet, and the love between the two provides an emotional constant in Cobb's world, which is otherwise ceaselessly shifting.

"Inception" works for the viewer, in a way, like the world itself worked for Leonard, the hero of "Memento." We are always in the Now. We have made some notes while getting Here, but we are not quite sure where Here is. Yet matters of life, death and the heart are involved--oh, and those multi-national corporations, of course. And Nolan doesn't pause before using well-crafted scenes from spycraft or espionage, including a clever scheme on board a 747 (even explaining why it must be a 747).

The movies often seem to come from the recycling bin these days: Sequels, remakes, franchises. "Inception" does a difficult thing. It is wholly original, cut from new cloth, and yet structured with action movie basics so it feels like it makes more sense than (quite possibly) it does. I thought there was a hole in "Memento:" How does a man with short-term memory loss remember he has short-term memory loss? Maybe there's a hole in "Inception" too, but I can't find it. Christopher Nolan reinvented "Batman." This time he isn't reinventing anything. Yet few directors will attempt to recycle "Inception." I think when Nolan left the labyrinth, he threw away the map.

Sunday, September 26, 2010

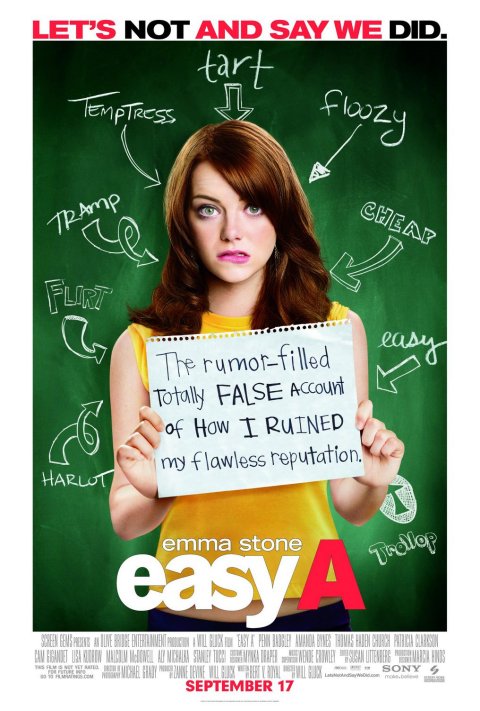

Easy A

"Easy A" offers an intriguing middle ground to the absolute of sexual abstinence: Don't sleep with anybody, but say you did. It's a funny, engaging comedy that takes the familiar but underrated Emma Stone and makes her, I believe, a star. Until actors are matched to the right role, we can never quite see them clearly.

Stone embodies Olive Penderghast, a girl nobody much notices at East Ojai High School. The biggest surprise about this school (apart from the fact that there is an East Ojai) is that it is scandalous to lose one's virginity in high school. I hesitate to generalize, but I suspect such a thing is not unheard of in East Ojai and elsewhere. I'm not recommending it. I only know what I'm told.

It is a rule with all comedies involving virginity, going back to Doris Day and long before, that enormous misunderstandings are involved and virginity miraculously survives at the end. In this case, Olive is simply embarrassed to admit she spent a whole weekend at home alone, so she improvises a goofy story about having lost her virginity to a college boy. That seems safe; nobody in school would know him. But she's overheard by Marianne (Amanda Bynes), a self-righteous religious type who passes the story round as an object lesson to wayward girls: Don't become a fallen woman like Olive.

"Easy A" takes this misunderstanding and finds effortless comic variations in it. The news is taken with equanimity by Olive's parents, Dill and Rosemary (Stanley Tucci and Patricia Clarkson), who join Juno's parents in the Pantheon of Parental Admirability. At East Ojai High, Olive finds that in having lost one reputation, she has gained another. Previously no one noticed her at all (hard to believe about Emma Stone, but there you have it). Now she is imagined to be an experienced and daring adventuress, and it can be deducted that a great many in the student body envy her experience.

Olive puts her notoriety to use. She has a gay friend named Brandon (Dan Byrd), who has been hassled at school (hard to believe in Ojai but, again, there you have it). By allowing word to get out that she and Brandon have shared blissful congress, she is able to bring an end to the bullying (hard to believe no one in East Ojai has heard of a gay and a straight having sex, but this Ojai is one created specifically for the convenience of a movie comedy, and people believe what the plot requires them to believe).

Now that she has become established as the school authority, she begins to issue a sort of Olive's Seal of Approval on various outsiders, misfits and untouchables in the student body, outfitting them all with credentials of sexmanship. Does anybody wonder why she only sleeps with gays, nerds and college students? Why should they? Lots of people do.

"Easy A," like many good comedies, supplies us with a more or less conventional (movie) world in which one premise — Olive's transformation by gossip — is introduced. She becomes endowed overnight with a power to improve reputations, confer status and help the needy. Her new power might even work for adults, such as the teacher Mr. Griffith (Thomas Haden Church) and his estranged wife (Lisa Kudrow), the guidance counselor, who become entangled in embarrassments.

The movie works because its funny, yes, but also because it's smart. When Olive begins wearing the scarlet letter "A" on her clothing, borrowing the idea from the Nathaniel Hawthorne novel they still read in East Ojai, she shows a level of irony that I'm afraid is lost on the student body, but not on us. I think it may always be necessary that we like the hero or heroine of a comedy. I certainly liked Olive. I'm pretty sure that's also how an actor becomes a movie star.

Stone embodies Olive Penderghast, a girl nobody much notices at East Ojai High School. The biggest surprise about this school (apart from the fact that there is an East Ojai) is that it is scandalous to lose one's virginity in high school. I hesitate to generalize, but I suspect such a thing is not unheard of in East Ojai and elsewhere. I'm not recommending it. I only know what I'm told.

It is a rule with all comedies involving virginity, going back to Doris Day and long before, that enormous misunderstandings are involved and virginity miraculously survives at the end. In this case, Olive is simply embarrassed to admit she spent a whole weekend at home alone, so she improvises a goofy story about having lost her virginity to a college boy. That seems safe; nobody in school would know him. But she's overheard by Marianne (Amanda Bynes), a self-righteous religious type who passes the story round as an object lesson to wayward girls: Don't become a fallen woman like Olive.

"Easy A" takes this misunderstanding and finds effortless comic variations in it. The news is taken with equanimity by Olive's parents, Dill and Rosemary (Stanley Tucci and Patricia Clarkson), who join Juno's parents in the Pantheon of Parental Admirability. At East Ojai High, Olive finds that in having lost one reputation, she has gained another. Previously no one noticed her at all (hard to believe about Emma Stone, but there you have it). Now she is imagined to be an experienced and daring adventuress, and it can be deducted that a great many in the student body envy her experience.

Olive puts her notoriety to use. She has a gay friend named Brandon (Dan Byrd), who has been hassled at school (hard to believe in Ojai but, again, there you have it). By allowing word to get out that she and Brandon have shared blissful congress, she is able to bring an end to the bullying (hard to believe no one in East Ojai has heard of a gay and a straight having sex, but this Ojai is one created specifically for the convenience of a movie comedy, and people believe what the plot requires them to believe).

Now that she has become established as the school authority, she begins to issue a sort of Olive's Seal of Approval on various outsiders, misfits and untouchables in the student body, outfitting them all with credentials of sexmanship. Does anybody wonder why she only sleeps with gays, nerds and college students? Why should they? Lots of people do.

"Easy A," like many good comedies, supplies us with a more or less conventional (movie) world in which one premise — Olive's transformation by gossip — is introduced. She becomes endowed overnight with a power to improve reputations, confer status and help the needy. Her new power might even work for adults, such as the teacher Mr. Griffith (Thomas Haden Church) and his estranged wife (Lisa Kudrow), the guidance counselor, who become entangled in embarrassments.

The movie works because its funny, yes, but also because it's smart. When Olive begins wearing the scarlet letter "A" on her clothing, borrowing the idea from the Nathaniel Hawthorne novel they still read in East Ojai, she shows a level of irony that I'm afraid is lost on the student body, but not on us. I think it may always be necessary that we like the hero or heroine of a comedy. I certainly liked Olive. I'm pretty sure that's also how an actor becomes a movie star.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Catfish

Here's one way to look at "Catfish." Some filmmakers in New York City, who think they're way cool, get taken apart by a ordinary family in Ishpeming, Mich. You can also view it as a cautionary tale about living your emotional life on the Internet. Or possibly the whole thing is a hoax. At Sundance 2010, the filmmakers were given a severe cross-examination and protested their innocence, and indeed everyone in the film is exactly as the film portrays them.

To go into detail about that statement would involve spoiling the film's effect for you. I won't do that, because the effect is rather lovely. There's a point when you may think you know what I'm referring to, but you can't appreciate it until closer to end. The facts in the film are slippery, but the revelation of a human personality is surprisingly moving.

The film opens in the Manhattan office of Nev Schulman, Ariel Schulman and Henry Joost, who make videos and photographs of modern dancers. I'm going to guess they're 30-ish. Nev has received a painting of one of his photographs from Abby Pierce, an 8-year-old girl. They enter into a correspondence — or, more accurately, Abby's mom, Angela Pierce, e-mails for her. Just as well. Would you want your 8-year daughter online with some strange adult Facebook friend?

Never mind. Nev is a wholesome, even naive man, is touched by Abby's paintings, and begins to identify with the whole family. He learns of school plans, pie baking, Sunday family breakfast, and the horse farm that Abby's 19-year-old sister, Megan, is buying. I doubted that detail. It would take a New Yorker to believe horse farms in Michigan are cheap enough for a 19-year-old to buy. She could afford a horse, farm not included.

Nev and Megan correspond and talk on the phone. Megan composes songs for Nev. They begin a cyber romance. Nev begins to wonder if this could possibly be the girl for him. There are dozens of photos on her Facebook site, and he even starts using software to put himself and Megan in the same photos. In anyone over, oh, 14, this is a sign of immaturity, wouldn't you say?

The three videographers have to fly to Vail to shoot a dance event. On the way back East, they decide to make a detour to Ishpeming. Were they born yesterday? Do they think you drop in unannounced on strangers? Using ever-helpful GPS navigation, they pay a midnight visit to Megan's horse farm, and find ... no horses. In Ishpeming, they do indeed find the Pierce home and family, and I suppose are welcomed with as much grace as possible under the circumstances.

The key to the human qualities in the film can be found in Angela, the mother, and in a couple of thoughtful statements by Vince, the father. You'll see what I mean. Living in Ishpeming may not be the ideal choice for people with an artistic temperament. I haven't been there and can't say. But this family has adapted to realities and found ways of expression, and who are we to say making dance videos in New York is preferable?

Angela Pierce comes across as an essentially good person, as complex as the heroine of a novel. At the end of the day, I believe she humbles Nev and his friends. I wonder if they agree. They all seem to be nice people. Let's agree on this: We deserve to share happiness in this world, and if we supply it in the way it's sought and nobody gets hurt, is that a bad thing?

To go into detail about that statement would involve spoiling the film's effect for you. I won't do that, because the effect is rather lovely. There's a point when you may think you know what I'm referring to, but you can't appreciate it until closer to end. The facts in the film are slippery, but the revelation of a human personality is surprisingly moving.

The film opens in the Manhattan office of Nev Schulman, Ariel Schulman and Henry Joost, who make videos and photographs of modern dancers. I'm going to guess they're 30-ish. Nev has received a painting of one of his photographs from Abby Pierce, an 8-year-old girl. They enter into a correspondence — or, more accurately, Abby's mom, Angela Pierce, e-mails for her. Just as well. Would you want your 8-year daughter online with some strange adult Facebook friend?

Never mind. Nev is a wholesome, even naive man, is touched by Abby's paintings, and begins to identify with the whole family. He learns of school plans, pie baking, Sunday family breakfast, and the horse farm that Abby's 19-year-old sister, Megan, is buying. I doubted that detail. It would take a New Yorker to believe horse farms in Michigan are cheap enough for a 19-year-old to buy. She could afford a horse, farm not included.

Nev and Megan correspond and talk on the phone. Megan composes songs for Nev. They begin a cyber romance. Nev begins to wonder if this could possibly be the girl for him. There are dozens of photos on her Facebook site, and he even starts using software to put himself and Megan in the same photos. In anyone over, oh, 14, this is a sign of immaturity, wouldn't you say?

The three videographers have to fly to Vail to shoot a dance event. On the way back East, they decide to make a detour to Ishpeming. Were they born yesterday? Do they think you drop in unannounced on strangers? Using ever-helpful GPS navigation, they pay a midnight visit to Megan's horse farm, and find ... no horses. In Ishpeming, they do indeed find the Pierce home and family, and I suppose are welcomed with as much grace as possible under the circumstances.

The key to the human qualities in the film can be found in Angela, the mother, and in a couple of thoughtful statements by Vince, the father. You'll see what I mean. Living in Ishpeming may not be the ideal choice for people with an artistic temperament. I haven't been there and can't say. But this family has adapted to realities and found ways of expression, and who are we to say making dance videos in New York is preferable?

Angela Pierce comes across as an essentially good person, as complex as the heroine of a novel. At the end of the day, I believe she humbles Nev and his friends. I wonder if they agree. They all seem to be nice people. Let's agree on this: We deserve to share happiness in this world, and if we supply it in the way it's sought and nobody gets hurt, is that a bad thing?

Friday, September 24, 2010

Buried

Buried alive. It must be a universal nightmare. I read Edgar Allan Poe's "The Premature Burial" when I was 7 or 8, and the thought troubled me for many a dark night. You are alive, you can move, you can scream, but no one will hear.

Paul Conroy is a truck driver working for a private contractor in Iraq. He comes to consciousness in blackness. He reaches out, feels, realizes. He finds a lighter. In its flame, his worst fears are realized. He finds a cell phone. He learns he has been kidnapped and is a hostage — in a coffin.

Obviously his captors want him to use the phone. They want to prove he is alive, because they plan to demand a ransom. By now we are identifying with Conroy's desperate thinking. Who can he call who can rescue him before the oxygen in the coffin runs out? Thankfully the coffin is longer than usual, allowing it to contain more air and also permitting certain camera angles that enhance the action.

Because there is action. Although the entire movie takes place in the enclosed space, director Rodrigo Cortes and writer Chris Sparling are ingenious in creating more plausible action than you would expect possible. They also allow themselves a few POV shots from outside the coffin — not on the surface, but simply from undefined darkness above the space.

Paul (Ryan Reynolds) uses the phone to call 911. The Pentagon. His employer's office. His wife. He receives calls from his kidnappers. These calls are exercises in frustration. There is nothing quite like being put on hold while you're buried alive.

It is the filmmakers' wise decision to omit any shots of the action at the other end of the calls. No shots of 911 operators, Pentagon generals or corporate PR types. No shots of his desperate kidnappers. No flashbacks to the ambush and kidnapping itself. No weeping wife. The movie illustrates the strength of audio books and radio drama: The images we summon in our minds are more compelling than any we could see. A seen image supplies satisfaction. An imagined one inspires yearning. Along with Paul, we're trying to transport ourselves to the other end of each call.

It would not be fair to even hint at some of the events in the coffin. Let it be said that none of them is impossible. There is no magic realism here. Only the immediate situation. The budget for "Buried" is said to be $3 million. In one sense, low. In another sense, more than adequate for everything director Cortes wants to accomplish, including his special effects and the voice talents of all the people on the other end of the line.

Ryan Reynolds has limited space to work in, and body language more or less preordained by the coffin, but he makes the character convincing if necessarily limited. The running time, 94 minutes, feels about right. The use of 2:35 wide screen paradoxically increases the effect of claustrophobia. I would not like to be buried alive.

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps

Oliver Stone's "Wall Street" (1987) was a wake-up call about the financial train wreck the Street was headed for. Had we only listened. Or perhaps we listened too well, and Gordon ("Greed Is Good") Gekko became the role model for a generation of amoral financial pirates who put hundreds of millions into their pockets while bankrupting their firms and bringing the economy to its knees. As "Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps" begins, Gekko has been able to cool his heels for many of the intervening years in a federal prison, which is the film's biggest fantasy; the thieves who plundered the financial system are still mostly in power, and congressional zealots resist efforts to regulate the system.

That's my point, however, and not Oliver Stone's. At a time when we've seen several lacerating documentaries about the economic meltdown, and Michael Lewis' The Big Short is on the best-seller lists, "Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps" isn't nearly as merciless as I expected. It's an entertaining story about ambition, romance and predatory trading practices, but it seems more fascinated than angry. Is Stone suggesting this new reality has become embedded, and we're stuck with it?

In some ways, Gordon Gekko himself (Michael Douglas) serves as a moral center for the film. Out from behind bars, author of Is Greed Good? and lecturer to business students, he at first seems to be a standard repentant sinner. Then he meets a young trader named Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf) and finds himself edging back into play. Jake wants to marry Gekko's daughter, Winnie (Carey Mulligan), who hasn't spoken to her father for years. Maybe Jake can be the conduit for their reconciliation. He sincerely loves Winnie, who is a liberal blogger. Jake himself is ambitious, already has his first million, wants more, but we see he has a good heart because he wants his firm to back alternative energy. Is this because he is green, or only likes it? A little of both, probably.

Jake works for an old-line Wall Street house named Keller Zabel, headed by his mentor and father figure Louis Zabel (Frank Langella). This firm is brought to its knees by a snake named Bretton James (Josh Brolin), who is instrumental in spreading rumors about its instability. Stone does not underline the irony that James' firm, and every Wall Street firm, is equally standing on a mountain of worthless debt. In a tense boardroom confrontation, Zabel is forced to sell out for a pittance. The next morning, he rises, has his soft-boiled egg, and throws himself under a subway train. It is instructive that although tycoons hurled themselves from windows during the Crash of 1929, the new generation simply continued to collect their paychecks, and Gekko expresses a certain respect for Zabel.

The death of his beloved mentor gives Jake a motive: He wants revenge on Bretton James, and suddenly all the parts come together: How he can hurt James, enlist Gekko, look good to Winnie, gain self-respect and maybe even make a nice pile of money along the way? It has taken an hour to get all the pieces in place, but Stone does it surely, and his casting choices are sound. Then the story hurries along as more melodrama than expose.

Michael Douglas of course is returning in an iconic role, and it's interesting to observe how Gordon Gekko has changed: just as smart, just as crafty, still with cards up his sleeve, older, somewhat wiser, keenly feeling his estrangement from his daughter. Shia LaBeouf, having earlier apprenticed to Indiana Jones and, at the beginning of this film, with Louis Zabel, falls in step eagerly beside Gordon Gekko, but may discover not everyone in his field wants to be his mentor.

Langella has little screen time as Zabel, but the character is crucial, and he is flawless in it. To the degree you can say this about any big player on Wall Street, Zabel is more sinned against than sinning. And then there's Carey Mulligan as Gekko's daughter, still blaming him for the death of her brother, still suspicious of the industry that shaped her father and now seems to be shaping Jake.

"Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps" is six minutes shorter than it was when I saw it at Cannes and has a smoother conclusion. It is still, we might say, certainly long enough. But it's a smart, glossy, beautifully photographed film that knows its way around the Street (Stone's father was a stockbroker). I wish it had been angrier. I wish it had been outraged. Maybe Stone's instincts are correct, and American audiences aren't ready for that. They haven't had enough of Greed.

That's my point, however, and not Oliver Stone's. At a time when we've seen several lacerating documentaries about the economic meltdown, and Michael Lewis' The Big Short is on the best-seller lists, "Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps" isn't nearly as merciless as I expected. It's an entertaining story about ambition, romance and predatory trading practices, but it seems more fascinated than angry. Is Stone suggesting this new reality has become embedded, and we're stuck with it?

In some ways, Gordon Gekko himself (Michael Douglas) serves as a moral center for the film. Out from behind bars, author of Is Greed Good? and lecturer to business students, he at first seems to be a standard repentant sinner. Then he meets a young trader named Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf) and finds himself edging back into play. Jake wants to marry Gekko's daughter, Winnie (Carey Mulligan), who hasn't spoken to her father for years. Maybe Jake can be the conduit for their reconciliation. He sincerely loves Winnie, who is a liberal blogger. Jake himself is ambitious, already has his first million, wants more, but we see he has a good heart because he wants his firm to back alternative energy. Is this because he is green, or only likes it? A little of both, probably.

Jake works for an old-line Wall Street house named Keller Zabel, headed by his mentor and father figure Louis Zabel (Frank Langella). This firm is brought to its knees by a snake named Bretton James (Josh Brolin), who is instrumental in spreading rumors about its instability. Stone does not underline the irony that James' firm, and every Wall Street firm, is equally standing on a mountain of worthless debt. In a tense boardroom confrontation, Zabel is forced to sell out for a pittance. The next morning, he rises, has his soft-boiled egg, and throws himself under a subway train. It is instructive that although tycoons hurled themselves from windows during the Crash of 1929, the new generation simply continued to collect their paychecks, and Gekko expresses a certain respect for Zabel.

The death of his beloved mentor gives Jake a motive: He wants revenge on Bretton James, and suddenly all the parts come together: How he can hurt James, enlist Gekko, look good to Winnie, gain self-respect and maybe even make a nice pile of money along the way? It has taken an hour to get all the pieces in place, but Stone does it surely, and his casting choices are sound. Then the story hurries along as more melodrama than expose.

Michael Douglas of course is returning in an iconic role, and it's interesting to observe how Gordon Gekko has changed: just as smart, just as crafty, still with cards up his sleeve, older, somewhat wiser, keenly feeling his estrangement from his daughter. Shia LaBeouf, having earlier apprenticed to Indiana Jones and, at the beginning of this film, with Louis Zabel, falls in step eagerly beside Gordon Gekko, but may discover not everyone in his field wants to be his mentor.

Langella has little screen time as Zabel, but the character is crucial, and he is flawless in it. To the degree you can say this about any big player on Wall Street, Zabel is more sinned against than sinning. And then there's Carey Mulligan as Gekko's daughter, still blaming him for the death of her brother, still suspicious of the industry that shaped her father and now seems to be shaping Jake.

"Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps" is six minutes shorter than it was when I saw it at Cannes and has a smoother conclusion. It is still, we might say, certainly long enough. But it's a smart, glossy, beautifully photographed film that knows its way around the Street (Stone's father was a stockbroker). I wish it had been angrier. I wish it had been outraged. Maybe Stone's instincts are correct, and American audiences aren't ready for that. They haven't had enough of Greed.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Legendary

Ah, the wrestling picture. In Joel and Ethan Coen's “Barton Fink,” a New York playwright is lured to Hollywood (for the cash) and is assigned to write a wrestling movie for Wallace Beery at Capitol Pictures. Audrey, the companion of the great Southern novelist-turned-screenwriter and epic alcoholic Bill Mayhew, explains the formula to Barton:

"Well, usually, they're… simple morality tales. There's a good wrestler, and a bad wrestler whom he confronts at the end. In between, the good wrestler has a love interest or a child he has to protect. Bill would usually make the good wrestler a backwoods type, or a convict. And sometimes, instead of a waif, he'd have the wrestler protecting an idiot manchild. The studio always hated that."

"Legendary" has most of that and lots more (minus the idiot manchild), turned inside out and all twisted up like a pretzel, but just as simple and formulaic. Yet even though this picture stars a real WWE wrestler and was produced by the new WWE Studios, it's not just a wrestling picture. ("Big men in tights!" as another Capitol Pictures executive exclaims.) It's a wrestling tearjerker.

The good wrestler, Mike Chetley (WWE superstar John Cena), is also the bad wrestler, estranged from his mother Sharon (Patricia Clarkson) and brother Cal (Devon Graye, who played the teenage anti-hero of "Dexter") since the death of his father ten years before. Picture the Arnold Schwarzenegger of "The Terminator" vintage as the elder sibling of a dyed-blond Justin Long. Cal is the size of Mike's left leg.

He's also the waif of the picture, but he's the good wrestler, too. In fact, he takes up wrestling as a way to get closer to his big (and I mean Big) brother, and attempts to rescue him from a limbo of booze, emotional demons and single-wide trailer living. So maybe it's the oversized, damaged Mike who's the idiot manchild in a way. Meanwhile, skinny bespectacled Cal has the only romantic interest, his kooky best friend since even-earlier-childhood, Luli (Madeleine Martin), who makes money by showing her newly sprouted boobs to boys in the woods and nurses a mighty crush on Cal, who doesn't think of her "in that way."

Add to this another hoary stereotype: the Wise Old Black Man and Narrator, Harry "Red" Newman (Danny Glover), who likes to go fishin' at the pond Cal keeps stocked with catfish. It's Red's job to call us "my friends" in voiceover and to elegiacally introduce the small-town, backwoods setting ("the spirit that is Oklahoma"), extoll the hearty disposition of the characters (Sooners are "an ambitious bunch of independent, strong-willed survivors") and announce the theme of the story ("some legends are born from struggle").

What more do you want to know? There is a bully who fills the role of the bad wrestler, only he's on the same Riverdale High School Tornadoes team as Cal, so they don't actually wrestle each other at the Big Match at the end. Along the way, I lost track of the number of musical training montages (fans of "Team America: World Police" will find themselves singing: "We're going to need a montage -- montage!"). And as Cal becomes a better wrestler, his eyesight improves, too. Soon, he no longer needs glasses.

It's a feel-good Kleenex™ dispenser of a movie, and there's nothing necessarily wrong with that, but it's routine Hallmark Hall of Afterschool Special material. What can an actor, even one as good as Patricia Clarkson, do with a line like, "There are things about Mike you don't know ... things Cal doesn't know," without sounding like Pee-wee Herman?

As far as action goes, there are a couple of very brief fight scenes in which Cena gets to throw some bad guys through plate glass and bang their heads on a bar. That's about it, except for some high school wrestling scenes, which are significantly less involving when you don't personally know the kids on the mat.

"Well, usually, they're… simple morality tales. There's a good wrestler, and a bad wrestler whom he confronts at the end. In between, the good wrestler has a love interest or a child he has to protect. Bill would usually make the good wrestler a backwoods type, or a convict. And sometimes, instead of a waif, he'd have the wrestler protecting an idiot manchild. The studio always hated that."

"Legendary" has most of that and lots more (minus the idiot manchild), turned inside out and all twisted up like a pretzel, but just as simple and formulaic. Yet even though this picture stars a real WWE wrestler and was produced by the new WWE Studios, it's not just a wrestling picture. ("Big men in tights!" as another Capitol Pictures executive exclaims.) It's a wrestling tearjerker.

The good wrestler, Mike Chetley (WWE superstar John Cena), is also the bad wrestler, estranged from his mother Sharon (Patricia Clarkson) and brother Cal (Devon Graye, who played the teenage anti-hero of "Dexter") since the death of his father ten years before. Picture the Arnold Schwarzenegger of "The Terminator" vintage as the elder sibling of a dyed-blond Justin Long. Cal is the size of Mike's left leg.

He's also the waif of the picture, but he's the good wrestler, too. In fact, he takes up wrestling as a way to get closer to his big (and I mean Big) brother, and attempts to rescue him from a limbo of booze, emotional demons and single-wide trailer living. So maybe it's the oversized, damaged Mike who's the idiot manchild in a way. Meanwhile, skinny bespectacled Cal has the only romantic interest, his kooky best friend since even-earlier-childhood, Luli (Madeleine Martin), who makes money by showing her newly sprouted boobs to boys in the woods and nurses a mighty crush on Cal, who doesn't think of her "in that way."

Add to this another hoary stereotype: the Wise Old Black Man and Narrator, Harry "Red" Newman (Danny Glover), who likes to go fishin' at the pond Cal keeps stocked with catfish. It's Red's job to call us "my friends" in voiceover and to elegiacally introduce the small-town, backwoods setting ("the spirit that is Oklahoma"), extoll the hearty disposition of the characters (Sooners are "an ambitious bunch of independent, strong-willed survivors") and announce the theme of the story ("some legends are born from struggle").

What more do you want to know? There is a bully who fills the role of the bad wrestler, only he's on the same Riverdale High School Tornadoes team as Cal, so they don't actually wrestle each other at the Big Match at the end. Along the way, I lost track of the number of musical training montages (fans of "Team America: World Police" will find themselves singing: "We're going to need a montage -- montage!"). And as Cal becomes a better wrestler, his eyesight improves, too. Soon, he no longer needs glasses.

It's a feel-good Kleenex™ dispenser of a movie, and there's nothing necessarily wrong with that, but it's routine Hallmark Hall of Afterschool Special material. What can an actor, even one as good as Patricia Clarkson, do with a line like, "There are things about Mike you don't know ... things Cal doesn't know," without sounding like Pee-wee Herman?

As far as action goes, there are a couple of very brief fight scenes in which Cena gets to throw some bad guys through plate glass and bang their heads on a bar. That's about it, except for some high school wrestling scenes, which are significantly less involving when you don't personally know the kids on the mat.

The American

"The American" allows George Clooney to play a man as starkly defined as a samurai. His fatal flaw, as it must be for any samurai, is love. Other than that, the American is perfect: Sealed, impervious and expert, with a focus so narrow it is defined only by his skills and his master. Here is a gripping film with the focus of a Japanese drama, an impenetrable character to equal Alain Delon's in "Le Samourai," by Jean-Pierre Melville.

Clooney plays a character named Jack, or perhaps Edward. He is one of those people who can assemble mechanical parts by feel and instinct, so inborn is his skill. His job is creating specialized weapons for specialized murders. He works for Pavel (Johan Leysen, who looks like Scott Glenn left to dry in the sun). Actually, we might say he "serves" Pavel, because he accepts his commands without question, giving him a samurai's loyalty.

Pavel assigns him a job. It involves meeting a woman named Mathilde (Thekla Reuten) in Italy. They meet in a public place, where she carries a paper folded under her arm--the classic tell in spy movies. Their conversation begins with one word: "Range?" It involves only the specifications of the desired weapon. No discussion of purpose, cost, anything.

He thinks to find a room in a small Italian hilltop village, but it doesn't feel right. He finds another. We know from the film's shocking opening scene that people want to kill him. In the second village, he meets the fleshy local priest, Father Benedetto (Paolo Bonacelli). Through him he meets the local mechanic, walks into his shop, and finds all the parts he needs to build a custom silencer.

In the village he also finds a whore, Clara (Violante Placido), who works in a bordello we are surprised to find such a village can support. Jack or Edward lives alone, does push-ups, drinks coffee in cafes, assembles the weapon. And so on. His telephone conversations with Pavel are terse. He finds people beginning to follow him and try to kill him.

The entire drama of this film rests on two words, "Mr. Butterfly." We must be vigilant to realize that once, and only once, they are spoken by the wrong person. They cause the entire film and all of its relationships to rotate. I felt exaltation at this detail. It is so rare to see a film this carefully crafted, this patiently assembled like a weapon, that when the word comes it strikes like a clap of thunder. A lesser film would have underscored it with a shock chord, punctuated it with a sudden zoom, or cut to a shocked close up. "The American" is too cool to do that. Too Zen, if you will.

The director is a Dutchman named Anton Corbijn, known to me for "Control" (2007), the story of Ian Curtis, lead singer of Joy Division, a suicide at 23. Corbin has otherwise made mostly music videos. Here he paints an idyllic Italian countryside as lyrical as his dialogue is taciturn. There is not a wrong shot. Every performance is tightly controlled. Clooney is in complete command of his effect. He sometimes seems to be chewing a very small piece of gum, or perhaps his tongue.

His weakness is love. Clara, the prostitute, should not be trusted. We sense he uses prostitutes because he made a mistake in the relationship that opens the film. In his business he cannot trust anybody. But perhaps Clara is different. Do not assume from what I've written that she isn't different. It is very possible. The film ends like a clockwork mechanism arriving at its final, clarifying tick.

Clooney plays a character named Jack, or perhaps Edward. He is one of those people who can assemble mechanical parts by feel and instinct, so inborn is his skill. His job is creating specialized weapons for specialized murders. He works for Pavel (Johan Leysen, who looks like Scott Glenn left to dry in the sun). Actually, we might say he "serves" Pavel, because he accepts his commands without question, giving him a samurai's loyalty.

Pavel assigns him a job. It involves meeting a woman named Mathilde (Thekla Reuten) in Italy. They meet in a public place, where she carries a paper folded under her arm--the classic tell in spy movies. Their conversation begins with one word: "Range?" It involves only the specifications of the desired weapon. No discussion of purpose, cost, anything.